We have calculated two different average speeds. Often when people say ‘average’ they mean one particular type. Think about other averages you have met - do either of these two calculations remind you of averages you already know?

For equal distance spent at each speed

\[\textrm{average speed} = \dfrac{2}{\dfrac{1}{46}+\dfrac{1}{62}},\]

and for equal time spent at each speed

\[\textrm{average speed} = \dfrac{46+62}{2}.\]

When people say ‘the average’ they are usually saying ‘the mean’. You know there is more than one type of average, but informally using ‘the average’ is often acceptable.

However it might surprise you that even saying ‘the mean’ is not enough, as there is also more than one type of mean. The mean you are most familiar with is actually called the ‘arithmetic mean’.

\[\text{arithmetic mean of $x_1$, ..., $x_n$ is } \dfrac{1}{n}(x_1 + x_2 + \dotsb + x_n).\]

You may have spotted that when finding the average for equal times, we arrived at \[\dfrac{46+62}{2},\] which is the arithmetic mean of \(46\) and \(62\).

What is probably less familiar is the scenario of equal distance which led to \[\dfrac{2}{\dfrac{1}{46}+\dfrac{1}{62}},\] which is the harmonic mean of \(46\) and \(62\).

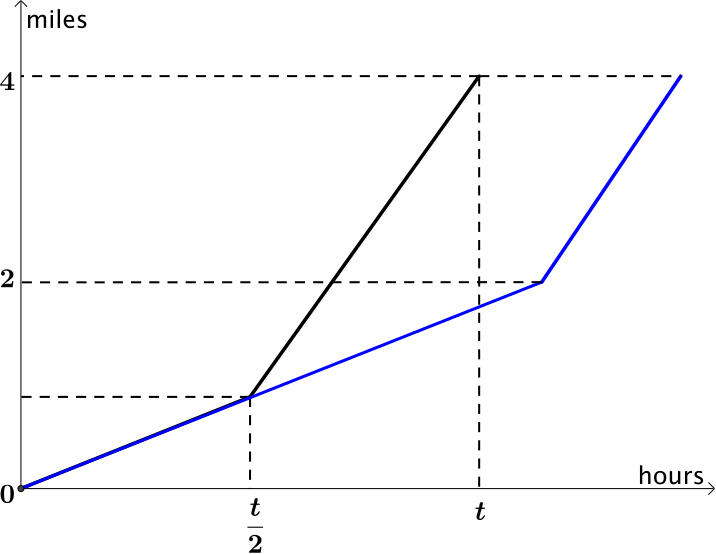

Let us make our driving examples more general. We already know that the distance does not affect the means when we are driving for an equal time or an equal distance.

If we make the speeds \(u\) and \(v\), what is the average speed when driving an equal time at each speed?

If our speeds remain \(u\) and \(v\), what is the average speed when each is driven for an equal distance?

Will one of the averages always be bigger than the other?

The result in the question above generalises to more than two speeds. In fact the harmonic mean is always less than or equal to the geometric mean, which is always less than or equal to the arithmetic mean for the same set of positive numbers.

The part of this result that is used the most often only involves the arithmetic and geometric means.

\[\dfrac{1}{n}(x_1 + x_2 + ... + x_n) ≥ \sqrt[n]{\vphantom{()}x_1x_2...x_n}\]

This is more commonly known as the AM-GM inequality, and appears more regularly than you might think. You might like to try this review question or this one that it appears in.

Let us now think about a type of question you may well have seen before.

If the (arithmetic) mean height of a class of 30 pupils is \(1.24\)m, and the mean height of a class of \(20\) pupils is \(1.42\)m, what is the mean height of all the pupils?

Now let us consider a car travelling at a speed \(u\) for a time \(t_1\) and then travelling at speed \(v\) for time \(t_2\). What is its average speed?

We have

\[u = \dfrac{d_1}{t_1} \textrm{ and } v = \dfrac{d_2}{t_2},\]

so the average speed is given by

\[\dfrac{d_1+d_2}{t_1+t_2}.\]

If we rearrange the formulae for \(u\) and \(v\) to get them in terms of \(d_1\) and \(d_2\) then we can substitute these into the formala for average speed to get

\[\dfrac{ut_1+vt_2}{t_1+t_2},\]

which can be written as

\[\dfrac{t_1}{t_1+t_2}\times u + \dfrac{t_2}{t_1+t_2}\times v,\]

which is a weighted arithmetic mean, where we are taking the proportion of time that has been travelled at each speed into account.

From this general case we can return to our special case of equal times.

If you make \(t_1 = t_2\), can you show the formula simplifies to the arithmetic mean?

If you start again, you can rearrange the formulae for \(u\) and \(v\) to get them in terms of \(t_1\) and \(t_2\), and so get a formula for average speed in terms of \(u\), \(v\), \(d_1\) and \(d_2\) that is a weighted harmonic mean. Can you return to our special case of equal distances from your formula?